Standards

1. (Re-)Positioning the Concept of Sustainable Development

Environmental, economic and community (social) interests will always intersect with each other. However, the continuity of these three often run in the opposite direction. Economic benefits often come first and tend to compromise environmental sustainability aspects. While environmental benefits often emerge as the antithesis of development that promotes economic progress. And the community is amidst these poles of benefits. The concept of sustainable development in the middle of these interests was the culmination of the journey of the previous 20 years when the UN Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm in 1972. This concept of sustainable development becomes a middle way of these three interests and later became the basis of the issuance of Rio Declaration that consists of 27 principles that will be a guide in the implementation of sustainable development.

In discussing the palm oil and biodiesel industry, all the principles in Rio declaration became very relevant. However, four laws are most relevant to the current development of the palm oil and biodiesel industry, namely:

Sustainable Development through Integration

In order to achieve sustainable development, environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it.

This principle emphasises the integration between development patterns and environmental protection efforts. This means that the implementation of development must be based on environmental protection and not two different things. In the biodiesel industry, this also means that efforts to protect the environment need to be an integrated part of the entire production chain. When looking at the current development of the biodiesel industry, this principle is then relevant to be reviewed.

Sustainable Patterns of Production and Consumption and Demographic Policies

To achieve sustainable development and a higher quality of life for all people, States should reduce and eliminate unsustainable patterns of production and consumption and promote appropriate demographic policies.

This principle has a specific emphasis, although it is almost like principle 4. The thing that can be underlined from this principle is to distinguish between developed and developing countries.[1] This means, even though the two classifications of the country need to prioritise a sustainable production-consumption pattern, the implementation would be different. It emphasises the word "demographic policy." That means, every demographic condition will have a quite striking difference. For example, level of population, level of purchasing power and so forth. In the biodiesel industry, the pattern of sustainable production and consumption becomes very significant. It is primarily related to the problem of providing raw materials for biodiesel and the safety of forest ecosystems. The design of palm oil production needs to look at the demographic situation of land availability in Indonesia.

Public Participation

Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.

This principle has gained full recognition within the framework of legislation in Indonesia. In the plantation, forestry and environment sectors, there are already rules that provide the basis for public participation. However, many criticise the implementation related to public involvement (especially in the forest and land management sector) which is still not optimal. [2]

Public involvement in the palm oil industry as the most critical part of the biodiesel industry in Indonesia is still lack. [3] In the downstream biodiesel industry, it is often found that consumers are not satisfied with the performance of biodiesel and the implementation scheme of biodiesel (complaints of engine damage and product scarcity). The complaint handling mechanism, in this case, is still not precise. In September 2018, BPDP-KS opened a call centre for complaints on the application of biodiesel.

The Environment and Trade

States should cooperate to promote a supportive and open international economic system that would lead to economic growth and sustainable development in all countries, to better address the problems of environmental degradation. Trade policy measures for environmental purposes should not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade. Unilateral actions to deal with environmental challenges outside the jurisdiction of the importing country should be avoided. Environmental measures addressing transboundary or global environmental problems should, as far as possible, be based on an international consensus.

This principle emphasises economic barriers through policies, especially regarding international trade. Looking at the dynamics of biodiesel, this principle seems to be relevant. In 2018, the dynamics of palm oil as a biodiesel feedstock were challenged by the European Union and the United States. Similarly, they also put an embargo to the palm oil-based biodiesel. Supposedly, the 12th principle of the Rio declaration could be a guideline for the Indonesian Government to place its position. Although this also means that a national strategy for viewing biodiesel as a national strategic issue needs to be done.

These four principles can be relevant keywords in looking at the dynamics of the biodiesel industry in Indonesia. To clarify the goals of sustainable development within the framework of national policy, Presidential Regulation No. 59 of 2017 on Implementation of Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (TPB) was issued. This regulation is a follow-up to the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012. A continuation of the 15-year journey of the 1997 Rio Declaration. This time, it is no longer just principles but has converged into the goal of sustainable development. At a national scale, it is translated into a policy framework that gives the mandate to develop the Sustainable Development Goals Roadmap 2017-2030 (Road Map), National Action Plan 2017-2019 to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (RAN TPB), and Regional Action Plan 2017-2019 to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (RAD TPB). All these operational documents will be aligned with the National Medium- and Long-Term Development Planning.

Principally, the concept of sustainable development has become more clearly defined on paper. TPB itself has 17 goals to realise sustainable development. Regarding the biodiesel and palm oil industry, there are at least four suitable goals that are closely related, namely the 7th goal on clean and affordable energy, the 12th goal on responsible production and consumption, the 13th goal on climate change mitigation and, the 15th goal of land ecosystems. The description of the achievement of these goals is outlined in the RAN TPB, RAD TPB, and Road Map. Until this report was written, the Roadmap and RAD TPB documents are still being drafted.

1.1 Indonesian Biodiesel Industry and Sustainable Development Goals

To be able to see the relevance of sustainable development goals with the dynamics of the national biodiesel policy, it is necessary to look at its position in the RAN TPB. The National Development Planning Agency issued the Regulation of the Minister of National Development Planning No. 7 of 2018 on Coordination, Planning, Monitoring, Evaluating and Reporting the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. This regulation forms the basis of guidelines for arranging RAD and Road Map, as well as being the legal basis for RAN TPB. In the description related to the challenges of achieving the 7th goal (clean and affordable energy), RAN puts the challenge of biofuel (including biodiesel) on the price difference which is still more expensive than fossil fuels. While the challenges for the application of new and renewable energy (EBT) related to land, the RAN document only identifies these challenges in the implementation of geothermal energy as its location in adjacent to the protected areas.

In identifying challenges from the renewable energy aspect, RAN document is still incomplete in looking at the underlying problems of renewable energy implementation in Indonesia. It is mainly related to the application of the biofuel industry (biodiesel). This is because land factors are also the biggest challenges in the implementation of biodiesel policies. On the contrary, RAN document emphasises the importance of increasing the biofuel (biodiesel) raw material productivity without identifying the overall issues found in downstream industries. In the target and direction of TPB policy, RAN document also does not pay much attention to the context of the overall implementation of the biodiesel policy. Three strategies are described to increase the role of new renewable energy, namely (i) implementing price policies and appropriate incentives to encourage investment in the field of new renewable energy; (ii) increasing the use of various new renewable energy for electricity generation; and (iii) increasing the utilisation of biofuel for transportation through Fuel-Blending biodiesel and bioethanol. From this direction, the upstream to downstream aspects that have contributed to the biodiesel policy in Indonesia has not received enough portion to consider.

In the matrix of government activities related to renewable energy, no action leads to a synergy between the upstream and downstream industries of biodiesel. This means, activities conducted by the government activities related to renewable energy, especially biofuel, are limited to increasing mixtures.

In the 12th goal on responsible production and consumption, two policy directions be opportunities in ensuring accountability of biodiesel products. Namely, the strategy of ecolabeling activities and the application of good cycle and good process principles. Both strategies can be part of realising sustainable biodiesel. Several large-scale palm oil plantation companies have implemented environmental sustainability policies on the internal company. The implementation of a good cycle and good process can be part of ensuring the accountability of biodiesel products and eliminating the assumption that biodiesel is not environmentally friendly. However, the RAN TPB document has not seen this opportunity as a strategy related to the biodiesel industry. This is proven by choice of ecolabel activities that are included in the framework of the policy is still limited to feasible in which is it is not a strong ecolabel for commodities, but instead leads to company's performance index related to the environment.

As for the 13th goal on dealing with climate change, steps for reducing emissions from across sectors include transportation and energy. Also, the increasing use of renewable energy is also a policy direction within the climate change handling framework. However, the policy is also directed at increasing the potential for carbon uptake from forest land simultaneously. This condition has not been fulfilled by the entire strategy framework of the goal. The fact that biodiesel is part of renewable energy in both transportation and energy sectors will still make it difficult to thrive when the issue of providing land has not been seriously considered. Moreover, when the existence of forest ecosystems is also part of emission reduction efforts. This context is then related to the 15th goal on land ecosystems. Because one of the challenges of the land ecosystem identified in the RAN TPB document is the high level of illegal acts and improved forest governance (including forest and land fires), this is one of the fundamental challenges of the upstream biodiesel industry. However, these four TPBs have not strategically considered the association of upstream and downstream industrial from biodiesel.

Given the description above, the integration spirit which becomes the keyword in the initial concept of sustainable development (principle 4) is not seen yet. The policy direction of each TPB in biodiesel is still sectoral, and the upstream and downstream biodiesel industries have not been integrated.

2. Realising Sustainable Development in the Palm Oil and Biodiesel Industry

As stated earlier, one of the models that can be an opportunity to create accountability for biodiesel products is to use sustainability standards. Although it cannot be a solution for all problems, a sustainability standard at least can provide a room for check and balances for the biodiesel industry. In this case, sustainability standards are needed to cover from upstream (plantation) to downstream (distribution). This means that the accountability system needs to provide a concrete picture that the biodiesel used has gone through a production process that is responsible for the environment and its ecosystem (good cycle and proper operation).

In this section, five standards related to the palm oil plantation and biodiesel industry will be discussed. Namely, the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil System (ISPO), the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomass (RSB), the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the International Standard for Carbon Certification (ISCC) and the Global Bio-Energy Partnership (GBeP). There are still some other standards that are not covered in this section, yet five of the criteria listed below are the most relevant and widely known on the issues of palm oil and biodiesel. We carry out a general classification of the topics in the standard. Using the ranking compiled by the International Trade Center (ITC), the principle consists of:[4]

- Ethics

- The ethical principle looks at the extent to which the company conducts its business by promoting business integrity and ethics. Some of the criteria in this classification include the completeness of the company's legality, licensing aspects, and company compliance with regulations that apply at the local, national and international levels.

- Environment

- The awareness and responsibility of business actors on environmental and conservation issues are the primary references used in various sustainability standards. Some of the benchmarks in this environmental classification include company policies to protect biodiversity around the area of their operations, handling and managing waste, and the company's efforts to maintain ecosystem conditions such as land, water, and forests.

- Social

- The social responsibility of the business actors for his workforce and the surrounding community is an important aspect used by various sustainability standards. This classification includes welfare guarantee, worker safety, community empowerment and the development of complaints/feedback mechanisms related to the efforts made.

- Economy

- The economic stability of the company is also one of the critical points to assess the sustainability aspects of the company. Some essential components of this classification include the level of the economic viability of the company, management of the company that puts forward the principle of sustainability, and how the company carries out its business activities at each stage of the business chain.

- Quality

- The awareness and commitment of businesspeople to the quality of the products they produce is also an important aspect. Some of the points included in this classification are company work productivity, audit system/periodic assessment, aspects of evaluation and monitoring of business activities, and transparency and traceability of product raw materials or other business components.

To analyse these five standards, interpretation of the classification above is carried out to understand the proportion of each principle that will be discussed in each measure. Besides, the weighting of the principles and indicators in the standard is also being conducted based on the classification of the urgency level in fulfilling the signs. This classification consists of deal-breaker, major, and minor. Indicators categorised as deal-breaker get three points, the weight for a significant category is two points, and one point for signs with the lowest level of urgency(minor).[5]

2.1 Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil System (ISPO)

The Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil Certification System (ISPO) is a certification system based on a set of principles, criteria, and indicators intended to be a standardisation system for the palm oil industry in Indonesia. This system is based on the Regulation of Ministry of Agriculture No. 11 of 2015 on ISPO. In the attachment to the regulation, the definition of ISPO is a business system in the field of palm oil plantations that are economically viable, socially feasible, and environmentally friendly based on the applicable laws and regulations in Indonesia. This system begins with the division of plantation classifications which are regulated through the Regulation of Ministry of Agriculture No. 7 of 2009 on Guidelines for Assessing Plantation Businesses. After a plantation business gets its classification, ISPO is then applied to plantation businesses that are required to have ISPO certificates.

As explained earlier, ISPO has two different approaches to other sustainability standards, namely voluntary and mandatory approaches. One important thing to note is that the obligation to have ISPO is excluded for plantation companies intended for renewable energy.[6] This means that ISPO scope to biodiesel business actors (as part of renewable energy) is voluntary.

With the wrong image of biodiesel in the international eyes community at the moment, palm oil companies that produce CPO for renewable energy must have ISPO. Thus, Indonesia's biodiesel supply chain will be guaranteed.

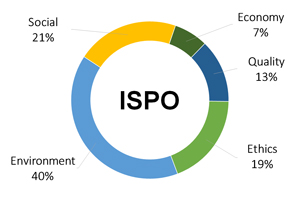

2.1.1 The Scope of ISPO

The diagram shows that the indicators of ISPO focuses on the classification of Environment, Ethics, and Social. The three classifications reach 80% out of all signs. As a sustainability standard under the Ministry of Agriculture, the indicators of ISPO are based on various laws and regulations that apply in Indonesia and are related to plantations (not just the Plantation Law). This also includes the Environmental Protection and Management Law, Forestry Law, and Spatial Planning. Hence, the basis of the indicators is the applicable laws and regulations. Some of more than a codification of laws. So that ISPO is only a check tool for completing the compliance of business actors with rules and regulations, and more accurately it can be said that ISPO referred to as a legality standard rather than sustainability standards.

Apart from these criticisms, since the indicators are based on laws and regulations in Indonesia, the scope of the principles and symbols in the ISPO also does not far different from what is required by statute. For ethical classification, ISPO includes but is not limited to business establishment permits (legal entities), location permits, environmental permits (including prerequisites such as Environmental Impact Analysis (AMDAL)), HGU, also plantation business permits such as IUP, IUP-B, and IUP-P. As for environmental classification, ISPO places principles and indicators that include but are not limited to the implementation of identification, management, and maintenance of water resources and quality, seed certification, SOP, and planting locations (mineral/peatland). While, as for social classification, principles and indicators of ISPO emphasise on the obligations of employers in implementing occupational, health and safety (OHS), OHS socialisation, OHS implementation reporting, provision of Social Security (Jamsostek), and maintaining environmental quality for residents of the community around the plantation.

This classification is probably not too appropriate to be applied to ISPO, mainly because of all the principles and criteria of ISPO based on Indonesian legislation. So that if classification is carried out strictly, almost 100% of the principles and standards in ISPO fall into the ethical classification. This is due to the proper classification covers various issues related to legality. However, this is not a rigid analysis as it still refers to the context of the problems of the principles and criteria of the ISPO.

2.1.2 Evaluation of ISPO Implementation

Many parties consider the implementation of ISPO which has been in operation for six years that this system has not resolved various fundamental problems of the Indonesian palm oil industry. In its development, in mid-2016, the government issued a policy to carry out a process of strengthening the ISPO. This policy arises due to the level of international market acceptance towards ISPO is very low. Many parties questioned on the accountability of the adoption of ISPO which still unable to respond many challenges in the palm oil plantation sector which should be minimised by the presence of sustainability standards.

Forest Watch Indonesia in its report found several facts that show that ISPO has not demonstrated sufficient performance about achieving its development goals as a certification system towards sustainable palm oil plantations. The registration and certification process, which runs very slowly, led to many occasions to clear new land. As for deforestation, during the 2009-2013 period, at least 516 thousand hectares of land were deforested in palm oil plantation concessions in which during that period ISPO was established, introduced and began to be implemented.[7]

2.2 Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)

RSPO is a non-profit organisation that unites stakeholders from the seven sectors of the palm oil industry: palm oil producers, processors or traders, consumer goods manufacturers, retailers, banks/investors, and environmental and social non-governmental organisations (NGOs).[8]

The RSPO was established in 2004 after being initiated by Aarhus United UK Ltd., Migros, Malaysian Palm Oil Association, Unilever, and WWF in 2001. Until 2018, RSPO has contributed to certifying 19% of the world's palm oil or as much as 12,2 million tons, where 51% of all CPO comes from Indonesia.[9]

The primary targets of the RSPO principles and criteria are palm oil plantations and mills. The RSPO scheme also draws commitment and support from various actors in the supply chain to the retailer even though not by meeting the principles and criteria directly. However, final product - oleo food- seems to be the focus of the RSPO is still the focus of the RSPO instead of biofuel. In this regard, the RSPO created an additional certification called the RSPO-RED Scheme.

The RSPO-RED scheme is a response to the requirements of the EU Directive 2009/28/EC as a form of promotion for renewable energy. The RSPO-RED scheme is designed to be used with the RSPO Principles & Criteria, RSPO Certification System requirements, RSPO Supply Chain Certification System requirements, and RSPO Supply chain Certification Standard. It is important to note that the RSPO-RED is a voluntary addition to all elements in the RSPO standard also applicable. The supply chain operation section that has RSPO-RED certification also certainly has RSPO certification for the same operating point.

The big difference between the RSPO scheme and the RSPO-RED scheme is on the issue of clearing new land and independent smallholders. As the requirements of the EU Directive on clearing new land are more complex, the RSPO-RED has not been able to certify land cleared after January 2008. The RSPO-RED has also not been able to certify independent smallholders as there are still many cases of documentation and administration that are not final. About the supply chain in this study, even with the addition of the RSPO-RED, the entire RSPO is still engaged in the downstream sector from palm oil plantations to B100 producers.

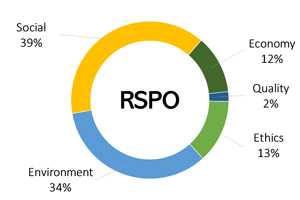

2.2.1 The Scope of RSPO

The emphasis on RSPO principles and criteria classification is not too different from ISPO, which is related to ethical, environmental and social ranking. 86% of the RSPO principles and indicators fall into these three classifications. But the social and ecological groupings are the largest. This is possible because ISPO principles and criteria focus more on responding to many problems related to environmental and social ranking. This does not mean that other classifications are not included in the RSPO. Their portion is just less. The RSPO-RED addition is not added because of its nature as a voluntary addition and the company participation for the RSPO-RED is still limited. There are also no companies that have RSPO- RED certification in Indonesia, compared to RSPO certification that reaches 36 plantation companies and 161 palm oil business entities from Indonesia.

In the context of market acceptance, RSPO principles and criteria are more accepted by the international market. Thus, most of the palm oil products that have received RSPO certification target the export market. Regarding the biodiesel industry, the RSPO-RED plays a vital role as a certification directed at the European market. But in its implementation, Europe then uses ISCC as the standard to be used concerning biodiesel.[10] Even so, the principles and criteria contained in the RSPO emphasise the upstream industry of biodiesel and do not cover the downstream biodiesel sector.

2.2.2 Evaluation of RSPO Implementation

As a multi-stakeholder forum, the RSPO has members who are not only palm producers. Civil society organisations can also become members of the RSPO, one of which is a civil society organisation from Indonesia, Sawit Watch. In 2013, Sawit Watch had some notes on the RSPO. The willingness of the RSPO is still weak to resolve conflicts that occur, there is no clear mechanism to protect groups of people affected by large-scale palm oil plantations, the application of double standards, not yet accommodating small farmers, and palm oil plantations workers who often become the object of palm oil company violence are not an RSPO priority yet.[11]

On the other hand, research from the University of Toulouse-II Le-Mirail - France, also saw the ineffectiveness of the RSPO in maintaining biodiversity conservation, especially in the Sumatran Orangutans case. This is due to several loopholes in the RSPO, namely lack of incentives (more cost must be spent to modify RSPO compared to the premium selling prices obtained from downstream industries), lack of precision on the guideline documents (there is still plenty of rooms for interpretation), delays in controversial issues, lack of integration with Indonesian legal-social-political context, and ineffective external control systems.[12]

2.3 International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC)

ISCC is a sustainability standard made through an open multi-stakeholder process that involves various stakeholders with approximately 250 international associations, corporations, research institutions, and NGOs. ISCC aims to contribute to the implementation of environmentally, socially and economically sustainable production and the use of all kinds of biomass in the global supply chain.[13]

ISCC was initiated in 2010, and to date, ISCC has issued more than 17,000 certifications in more than 100 countries (including Indonesia) for various raw materials. The number of companies that obtain certification for palm oil until 2018 is 357 companies.[14]

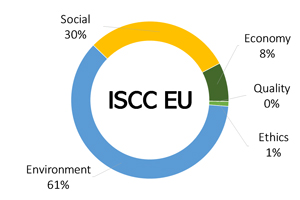

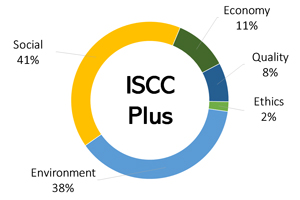

There are two types of ISCC certification commonly used, namely ISCC Plus and ISCC EU. The difference between the two certifications is the target market, where the products will be marketed. ISCC Plus can be used for food, feed, bio-energy products, and biofuel markets outside Europe while ISCC EU is designed to target the biofuel market within the EU as it is following the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and Fuel Quality Directive (FQD).[15]

2.3.1 The Scope of ISCC

In addition to differences in the marketing objectives of a product, the difference between ISCC EU and ISCC Plus lies in the proportion of each classification principle in the ISCC standard. ISCC EU emphasis much on the environmental aspect because of RED requirements that are also quite high. Zero deforestation, essential ecosystem areas, and conservation areas are some of the elements in the RED and being accommodated in the ISCC EU. Conversely, due to ISCC Plus is not subject to RED provisions (which only applicable in EU member states), the emphasis on the environmental aspects is lower. However, the differences in the proportions of both are not very significant and have a lot of influence.

In the biodiesel context, ISCC is the basis for assessing biodiesel products coming from Indonesia. While the emphasis on ISCC principles, criteria and indicators remain on plantation aspect, this means, the ISCC scope is not too different than the RSPO. The expectation that ISCC will have a specific standard assessment for biodiesel products so far is still not clear.

ISCC EU is very focused on indicators related to the environment, which reaches 61% out of all signs. ISCC EU has greater attention to environmental issues compared to ISCC Plus aimed at outside European markets.

For the environmental classification, the principles and criteria in the ISCC are not too different from RSPO, yet it has deeper scope for some items. For example, the principles and indicators related to forests. ISCC includes discussions about increasing conservation in forest ecosystems, conversion for agricultural needs, assessment of forest management plans, and public consultations related to forest planning. Assessed from the supply chain, the principles and criteria of ISCC are targeting plantations that are expected to have an impact on all supply chain components. This target is more achievable for food products such as cooking oil, but, the ISCC certification is not sufficient for BUBBN producing biodiesel products.

2.3.2 Evaluation of ISCC Implementation

The number of organisations that highlighted the implementation of ISCC both in Indonesia and in international scale is still small. Some records found related to the implementation of ISCC have so far been felt by the domestic actors. One of the opinions that emerged regarding the implementation of the ISCC was the increasing challenge of the Indonesian palm oil industry since ISCC international certificate is compulsory.[16] The principles and criteria emphasised by ISCC do not have a significant difference. One study related to sustainability standards and palm oil commodities in Indonesia illustrates the comparison of the RSPO with ISCC as below:

But the comparison does not necessarily have high precision. Because for example when looking at the measurement of greenhouse gases (GHG), the RSPO has criteria for carrying out these calculations. That is, a striking difference from the two standards is also not very visible. It is not surprising that businesses see it more as an additional burden and tend to be thicker with the nuances of international trade politics.

Comparison of RSPO and ISCC

| Standard | External Transparency | Environmental Criteria | Social Criteria | Strictness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSPO | Principles and Criteria are published, including audit results and accessible to the public |

|

|

32 of the 39 criteria must include more than 1 mandatory indicator. 45% of all indicators are mandatory |

| ISCC | Only published criteria (due to copyright reasons) |

|

|

"Major" fulfilment must meet 57 of 107 criteria and 60% of "minor" category |

| Source: Sustainability Certification in the Indonesian Palm Oil Sector, Benefit and Challenge for Smallholders.[17] | ||||

2.4 Global Bioenergy Partnership (GBeP)

However, the comparison does not necessarily have high precision. For example, when looking at the measurement of greenhouse gases (GHG), the RSPO has criteria for the calculation. It means a striking difference between the two standards is also not very visible. It is not surprising that businesses see it more as an additional burden which more likely has the nuances of international trade politics:

"... The indicators are value-neutral, do not feature directions, thresholds or limits and do not constitute a standard, nor are they legally binding."[18]

From this explanation, even GBeP stated explicitly that this initiative was not a standard. Apart from this uniqueness, GBeP needs to be part of international efforts to provide a direction towards bioenergy utilisation that considers environmental, social and economic balance. There are 24 sustainability indicators in GBeP which are divided into three important principles, namely environmental, economic, and social. To homogenise the even though GBeP only consists of three major themes, we will look at the context to adjust to the existing classification.

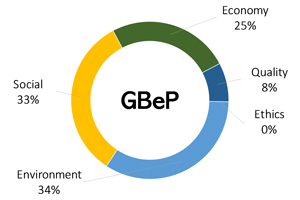

2.4.1 The Scope of GBeP

The diagram shows that the classification component of the principles and indicators in GBeP has the most significant weight in environmental, economic and social aspects. The aspects related to ethics (including legality) are not part of GBeP, while the elements related to quality of portion are minimal. Through this classification, GBeP emphasises on three pillars of sustainable development and seeks its midpoint regarding the biodiesel industry.

In the environmental classification, GBeP scope includes the aspects of soil quality, life cycle emissions, water quality, water use, biodiversity protection, and land conversion for biodiesel raw material needs. As for the land conversion, GBeP has a different approach than the other standards since it fits in the context of the biodiesel industry. For example, for the land aspect, GBeP provides direction in its indicators for the government to see the availability of land intended for biodiesel feedstock.

In the social classification, GBeP scope includes the allocation of community land associated with palm oil industry, commodity supply prices, increased income, and the provision of jobs related to the biodiesel sector. The rule of jobs in the biodiesel industry also becomes a unique indicator since other sustainability standards do not possess it. Whereas in the industrial classification, most of the scope of the GBeP indicator is not too different from some other signs. The thing that stands out is that the characteristics of the indicators that are seen are indeed adjusted for the needs of upstream and downstream industries of biodiesel.

Looking at the specifications of GBeP, from several sustainability standards that exist, GBeP has the most contextual specs for biodiesel industry whose scope is from upstream to downstream. However, the indicator is necessary to incorporate legal aspects. Because the legality aspect is one of the essential elements as this aspect has become the root of many problems in Indonesia.

2.4.2 Evaluation of GBEP Implementation

The implementation of GBeP in the context of the dynamics of the biodiesel industry in Indonesia is still not visible. Since its appearance in 2008, the application of GBeP has not been too significant. One publication that gives attention to GBeP is looking at the compatibility of GBeP in Indonesia. [19]The research conducted by the Bogor Agricultural Institute, Agroindustry Department shows that the level of compatibility of GBeP to be implemented in Indonesia is high. Analyzed using Mamdani FIS (Fuzzy Inference System). [20] . This means, compared to several other existing standards, GBeP has balanced principles and criteria concerning the pillars of sustainable development (social, economic, environmental).

Although the analysis shows that GBeP has high compatibility in Indonesia, but GBeP has the uncommon nature of standard and only serves as a guide that needs to be followed up at national-level policy. The government has by far not made clear steps to provide a policy foundation in implementing GBeP in biodiesel industry in Indonesia.

2.5 Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB)

RSB is an independent international organisation that implements and develops sustainability standards for biofuel-based industries (biomaterials). The criteria possessed by the RSB include the utilisation of biofuel including but not limited to biofuel itself. RSB has a voluntary nature and follows market mechanisms as other sustainability standards. That means the implementation of RSB is in the realm of producers who want certification of their products. However, the influence of RSB is quite extensive in the context of policy making because its acceptance in the international market is quite extensive as well.{footnoteRoundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), RSB Outcome Evaluation Report, Geneva, 2015.{/footnote}

In the context of the biodiesel industry, RSB is one of the voluntary certification schemes that can support the direction of the EU-RED (in addition to the ISCC scheme).[21] Also, in 2012, RSB conducted a project in Ethiopia named Sustainable Biofuels in Ethiopia. This study has identified gaps related to principles' standard regarding planning, monitoring, and sustainable improvement; rural and social development; food security; conservation; use of input/technology; land rights and land use rights. This project aims to carry out stakeholder mapping related to biofuels and simultaneously build a road map for the implementation of biofuels in Ethiopia. One of the important things to highlight from this project is that the principle of free and prior informed consent is still needed to be done concerning land rights.[22]

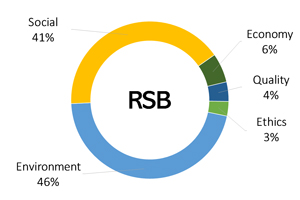

2.5.1 The Scope of RSB

The graphic shows the RSB focuses most on the environmental and social aspect. Like other sustainability standards for the palm oil industry, the RSB principles lie on legality, sustainable improvement, GHG emissions, human rights, social development, conservation, land, water, air, waste, and land rights. One of the differences with other environmental sustainability standards is the calculation of GHG life cycle. Another unique thing, RSB clearly describes which principles and indicators apply to biomass producers, factories or both. In this regard, almost all the principles and indicators of RSB are designed to be able to be met by all supply chain elements.

2.5.2 Evaluation of RSB Implementation

Also, in Indonesia context, there are no organisations or companies that are members of the RSB. However, RSB has a measurement system for the impact of the implementation of RSB. In 2015, this system generated an evaluation report on the implementation of the RSB. The thing that can be highlighted in this evaluation is that RSB is still not able to penetrate the market optimally, so this standard is just a formality rather than as a driver of change.[23]

3. Seeing Sustainability Standards in the Downstream and Upstream of Biodiesel Industry

As described in the previous section, the dynamics of the biodiesel industry correlates upstream and downstream sectors. The practices that carried out on the upstream as a supplier of raw materials will affect the downstream issue, particularly related to consumer acceptance of environmentally friendly biodiesel products. In this context, the sustainability standard which is expected to be one of the tools to create sustainable biodiesel is also likely to have upstream to downstream coverage. From the graphic above, it shows the scope of each standard analysed in this section. The darker colours indicate that the weight given to these indicators on a rule is stable, while the lighter colours show that the pressure of the indicators is getting weaker. The weight referred here is the number of indicators that regulate each point along the biodiesel supply chain.

In general, only GBeP and RSB indicators that cover the upstream to downstream. However, it is also noticed that the weight of indicators of both GBep and RSB does not give enough pressure to the downstream. This means that the centre of gravity remains consigned to the upstream biodiesel industry. This condition then becomes a point of compromise, because if the weight becomes equal between upstream and downstream, the implementation of the standard will be complicated. In this case, GBeP appears to be a reasonably rational standard in providing indicator weights. However, the weakness of GBeP is not placing the legal aspect in the indicator. Thus, even on the upstream side, the importance of the index is not too healthy. Also, the nature of GBeP which is not a standard becomes a weakness so that its implementation will depend on the goodwill of the government.

For other sustainability standards, the scope is focused on the upstream biodiesel industry. Although in each measure there are differences in giving weight at each stage in the biodiesel supply chain. The rule seems to see the main problem of the palm oil industry lies in its upstream side because it is related to raw materials. Several indicators are approaching the downstream but only limited to the scale of the biodiesel plant.

Although both deemed to reach BU-BBN, RSPO and ISCC have different approaches to ISPO. This is because the second certification scheme has the basic principle of collaborating with manufacturing plants to ensure sustainability for end consumers. However, the system has not been reflected in the biodiesel industry in Indonesia, but rather it is implemented to food products and directed towards the export market. In the end, RSPO and ISCC certification will stop at BUBBN.

On the legal aspect, all standards (except GBeP) require that companies to comply with all administrative regulations applicable in the relevant the country. ISPO becomes the most specific and widely used regulation. This is undoubted because ISPO is made in Indonesia for plantation companies in Indonesia, so unlike other international sustainability standards, it does not require interpretations for implementation at the national level. The legal side in sustainability standards in Indonesia is of concern as evidenced by the high number of independent smallholders or even plantation companies that do not have proper administrative documentation. This issue has made the palm oil industry in Indonesia often found in a grey area in the context of environmental sustainability. The legality and administration of land can be used as the first stage of screening for palm oil plants in selecting farmers as their suppliers.

Important notes should be made on the criteria for land clearing, deforestation, use of peat land and land burning. ISPO and RSPO still allow the clearance of new territory. In this matter, RSPO has more specific principles than ISPO. ISPO does not allow the use of fire in the land preparation or during replanting, while RSPO and ISCC still allow the practice with various limitations. The RSB is still within limits according to the advice and recommendations on the restrictions on the use of open fire for the burning of residue, waste, or land preparation. Land with high conservation value and carbon stock is also discussed at ISCC but not at ISPO and RSPO.

3.1 Principles that must be included in Sustainability Standards

Looking at the five examples of existing sustainability standards, it can be seen that there are at least five principles that underlie the current rules, namely 1) legality, 2) environment, 3) protection of human rights for workers, 4) social protection and affected communities' protection, and 5) economy. The emphasis on the five basic principles differs from one standard to another. Therefore, it is necessary to have a shared vision between palm-oil industry actors in general and the biodiesel industry to find out what basic principles need to exist.

A discussion held with civil society organisations on the issue of sustainability standards in the biodiesel industry has managed to agree on the following matters:

1. The main priority is the upstream sector as the provider of raw materials

Considering the dynamics of the biodiesel industry, the main priority is, therefore, to ensure that the supply of FFB to be used to produce biodiesel has met sustainability standards. However, this does not mean that coverage of the downstream becomes irrelevant. It is made as the second priority.

2. Strengthening of institutions and political will in standard implementation

Learning from the application of various standards, the institutional aspect plays an important role. Because without strong institutional elements, sustainability standards are only used as a tool for businesses to manage their good image. Hence, a strong institution and political will to deal with complaints and problems are the keys to the success of a sustainability standard.

3. Strengthening of indicators at each supply chain point is essential to do

The fact that nowadays various measures will be a problem in the implementation. Notably, the biodiesel industry has quite extensive coverage. In the end, this situation will create a burden for businesspeople in implementing the standards. Thus, the strengthening of indicators needs to be considered. Therefore, it is possible to enrich a standard by adding indicators found in other measures.

It is not easy to visualise the realisation of the upstream to downstream of the biodiesel industry that is well integrated and planned. Nevertheless, it is a mandatory step since biodiesel is a national strategic industry. All elements and sectors must be engaged in the integration process. Sustainability standards cannot be a panacea for all the challenges in the biodiesel industry. However, the sustainability standards at least give opportunity for the enforcement to accountability and, checks and balances mechanisms in the context of biodiesel products in Indonesia.

Footnotes:

| 1. | Jorge E. Viñuales, "The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development" [accessed on 27 August 2018]. (kembali) Jorge E. Viñuales, "The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development" [accessed on 27 August 2018]. |

| 2. | Putu Oka Ngakan, Heru Komarudin, Amran Achmad, Wahyudi dan Akhmad Tako, Dependency, Perception and Community Participation in Forest Biological Resources: A Case Study in Pampli, North Luwu Regency, South Sulawesi, Jakarta: Center for International Forestry Research, 2006. (kembali) Putu Oka Ngakan, Heru Komarudin, Amran Achmad, Wahyudi dan Akhmad Tako, Dependency, Perception and Community Participation in Forest Biological Resources: A Case Study in Pampli, North Luwu Regency, South Sulawesi, Jakarta: Center for International Forestry Research, 2006. |

| 3. | Walhi, "The Views and Input of the Civil Society Coalition on the Palm Oil Moratorium Policy Plan" [accessed on 27 August 2018]. (kembali) Walhi, "The Views and Input of the Civil Society Coalition on the Palm Oil Moratorium Policy Plan" [accessed on 27 August 2018]. |

| 4. | International Trade Center. (2017). Trade for Sustainable Development, "Trade for Sustainable Development" [accessed 27 August 2018]. (kembali) International Trade Center. (2017). Trade for Sustainable Development, "Trade for Sustainable Development" [accessed 27 August 2018]. |

| 5. | Basically, the ITC (which develops the five classifications) has interpreted the classifications compiled. But for the sake of objectivity and practicality, this study reinterpreted. So that referring to identification from the ITC is only classification and weighting. (kembali) Basically, the ITC (which develops the five classifications) has interpreted the classifications compiled. But for the sake of objectivity and practicality, this study reinterpreted. So that referring to identification from the ITC is only classification and weighting. |

| 6. | Ministry of Agriculture, Minister Regulation of Agriculture No. 11 of 2015 on ISPO, article 2, paragraph (3c). (kembali) Ministry of Agriculture, Minister Regulation of Agriculture No. 11 of 2015 on ISPO, article 2, paragraph (3c). |

| 7. | }Soelthon Gussatya Nanggara et al., Six Years ISPO, Bogor: Forest Watch Indonesia, 2017. (kembali) }Soelthon Gussatya Nanggara et al., Six Years ISPO, Bogor: Forest Watch Indonesia, 2017. |

| 8. | Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), "About" [accessed on 26 July 2018]. (kembali) Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), "About" [accessed on 26 July 2018]. |

| 9. | Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), "Our Impact" [accessed on 26 July 2018]. (kembali) Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), "Our Impact" [accessed on 26 July 2018]. |

| 10. | Sangeetha Amarthalingam, "Expect EU single certification to be stricter than RSPO — expert" [accessed 25 August 2018]. (kembali) Sangeetha Amarthalingam, "Expect EU single certification to be stricter than RSPO — expert" [accessed 25 August 2018]. |

| 11. | Maryo Saputra, "Reading Material and Evaluation of Palm Oil Watch for 9 Years at RSPO" [accessed on 10 August 2018]. (kembali) Maryo Saputra, "Reading Material and Evaluation of Palm Oil Watch for 9 Years at RSPO" [accessed on 10 August 2018]. |

| 12. | Denis Ruysschaert dan Denis Salles, "Towards global voluntary standards: Questioning the effectiveness in attaining conservation goals - The case on the Rountable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)", Elsevier, Volume 107, (Science Direct: Ecological Economics), 2014, p. 438-446. (kembali) Denis Ruysschaert dan Denis Salles, "Towards global voluntary standards: Questioning the effectiveness in attaining conservation goals - The case on the Rountable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)", Elsevier, Volume 107, (Science Direct: Ecological Economics), 2014, p. 438-446. |

| 13. | International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Objectives" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. (kembali) International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Objectives" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. |

| 14. | International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Transparency & Impact" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. (kembali) International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Transparency & Impact" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. |

| 15. | International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Recognitions" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. (kembali) International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC), "Recognitions" [accessed on 31 July 2018]. |

| 16. | Suara Pusaka, "These are the ISPO Compulsory and Voluntary Certification Criteria for Oil Palm Companies in Indonesia" [accessed on 13 April 2018]. (kembali) Suara Pusaka, "These are the ISPO Compulsory and Voluntary Certification Criteria for Oil Palm Companies in Indonesia" [accessed on 13 April 2018]. |

| 17. | Clara Brandi et al., Sustainability Certification in the Indonesian Palm Oil Sector: Benefits and challanges for smallholders, Jerman: Deutsche Institut für Entwicklungspolitik - German Development Institute, 2013. (kembali) Clara Brandi et al., Sustainability Certification in the Indonesian Palm Oil Sector: Benefits and challanges for smallholders, Jerman: Deutsche Institut für Entwicklungspolitik - German Development Institute, 2013. |

| 18. | }Global Bioenergy Partnership (GBEP), The Global Bioenergy Partnership Sustainability Indicators for Bioenergy, Italia: Food and Agriculture of United Nations, 2011. (kembali) }Global Bioenergy Partnership (GBEP), The Global Bioenergy Partnership Sustainability Indicators for Bioenergy, Italia: Food and Agriculture of United Nations, 2011. |

| 19. | Y Arkeman, R A Rizkyanti dan E Hambali, "Determination of Indonesian palm-oil-based bioenergy sustainability indicators using fuzzy inference system", IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volume 65, Number 1, 2019. (kembali) Y Arkeman, R A Rizkyanti dan E Hambali, "Determination of Indonesian palm-oil-based bioenergy sustainability indicators using fuzzy inference system", IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volume 65, Number 1, 2019. |

| 20. | Mamdani dan Sugeno, "4. Fuzzy inference systems" [accessed on 13 April 2018]. (kembali) Mamdani dan Sugeno, "4. Fuzzy inference systems" [accessed on 13 April 2018]. |

| 21. | Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), The Year of Impact: Reviewing 2016, Geneva, 2016. (kembali) Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), The Year of Impact: Reviewing 2016, Geneva, 2016. |

| 22. | Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels (RSB), Towards Sustainable Biofuels in Ethiopia, Energy Center EPFL, 2017. (kembali) Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels (RSB), Towards Sustainable Biofuels in Ethiopia, Energy Center EPFL, 2017. |

| 23. | Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), loc. cit. (kembali) Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), loc. cit. |